The Magic of the Broth

Written by Jack Forbes

Often, it’s the things that go unnoticed in the little moments that linger longest and macerate with memory into myth. I remember the weekly routine of visiting Granma’s every Sunday as a kid. These visits meant running through the scullery faster than my brothers to be the first to find out what chocolaty treats were waiting for us; Granma’s biscuit tin was always the legend we shared between us. It was hard to get past the obsession with everything that made our teeth rot, and until our teenage years, my brothers and I lived for sweets. But now, as I sit, years later, and reflect on those times, it’s the smell of Granma’s homemade broth that sits strongest at the back of my mind, outlining her wee living room, shaping the mantelpiece with the early-afternoon light, and bringing me back to those loud Sunday lunches in Hazleheid.

Every weekend, it was the same story: we would all pile into Granma’s small tenement, populate her living room and wait excitedly for the arrival of the biscuit tin. Always, her silhouette would appear through the frosted glass door with much more than just the biscuit tin. My favourite, the familiar wave of blue and orange Jaffa Cakes would appear, sometimes caramel logs, often chocolate Jeffers. All would be piled up to Granma’s chin as she shuffled in from the scullery to shower us with treats. While we were distracted inhaling a month’s worth of calories, the staple smell of the place – that broth soup fragrance- would waft in unnoticed and settle all around us, as common as the walls.

The four of us would demolish kilograms of chocolate, and Granma would perch off the edge of the sofa, a scalding cuppa of seven-second-steeped tea clutched tight between her fingers. She would sway quietly back and forth, a huge grin on her falsers.

“Aye aye, eat up”, she would say if we showed any signs of slowing down in the sugar intake. “There’s some Magnums in the freezer for after.” Our delicious antipasto of chocolate would conclude, and Granma would disappear to check on the main course.

Food was never glamorous with Granma. We would often each get a small Marks and Spencer pizza with oven chips for our lunch. At some point, for whatever reason, Granma had colluded with the fates and decided that I was to be the chief pizza inspector. Every time while she was preparing our lunch, she would pop her head in through the living room door as our eyes were glued to our seven-hundredth screening of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film and would say something like: “Jack, could you come ben the hoose and check on the pizzas.” I would jump up and quickly dive through to the kitchen – there was no chance of the video being paused. I would take out my pizza inspection checklist, open the oven, and as a blast of air carried a warm ripple through my fringe, I would announce, “Aye, they look perfect Granma.” She would nod her head in agreement, shoo me away, and a few minutes later appear with a small pizza for each of us and slyly slide in a bowl of her inconspicuous broth soup. She would return to her perch on the sofa with a tiny bowl of broth and maybe a half slice of buttered toast. I remember asking her once: “Do you not want a slice of pizza Granma?” I also remember her look of disgust as she replied, “No, no, no, I dinnah want any o’ that modrin (modern) rubbish.”

In the very early days, before Granma branched out internationally with the pizzas, when Granda was still around, the broth was always the centrepiece of a Sunday lunch. Granda would be seated in his wheelchair in the middle of the room – the fold-away table set up – his head bowed down, fully immersed in the culinary delight of the broth. Between deep slurps, melodic exclamations of “beautiful” would fill the room. Granda’s reverence for the broth is one of the few recurring memories I have left of him, and therefore this ritual is one my brothers and I still carry on. Over the years, whenever the four of us have been together, broth or not, declarations of “beautiful” have been passed around the table to remember and relive Granda’s appreciation for the broth. It forever cracks us up.

Whether it was Christmas, one of our birthdays or even just a random holiday that sat outside the usual Sunday schedule, Granma would always have a bag of sweets, a selection box, a mesh bag of chocolate coins or a pick n’ mix ready for us. We would always swallow these up without thought. Then, as we crashed from a seesaw of sugar rushes, she would produce from her bag a frozen Tupperware of the broth. As we grew up, so did our reverence for the broth, and we would beg Granma to heat it up on the stove, no matter the time of day. There was something special about the broth that the Mars Bars, Starburst or bags of Skittles could not touch. Its lingering saltiness and depths of mouth-watering warmth would always dance for hours over my taste buds. I always longed for more, especially on those cold Scottish afternoons. I can taste it still.

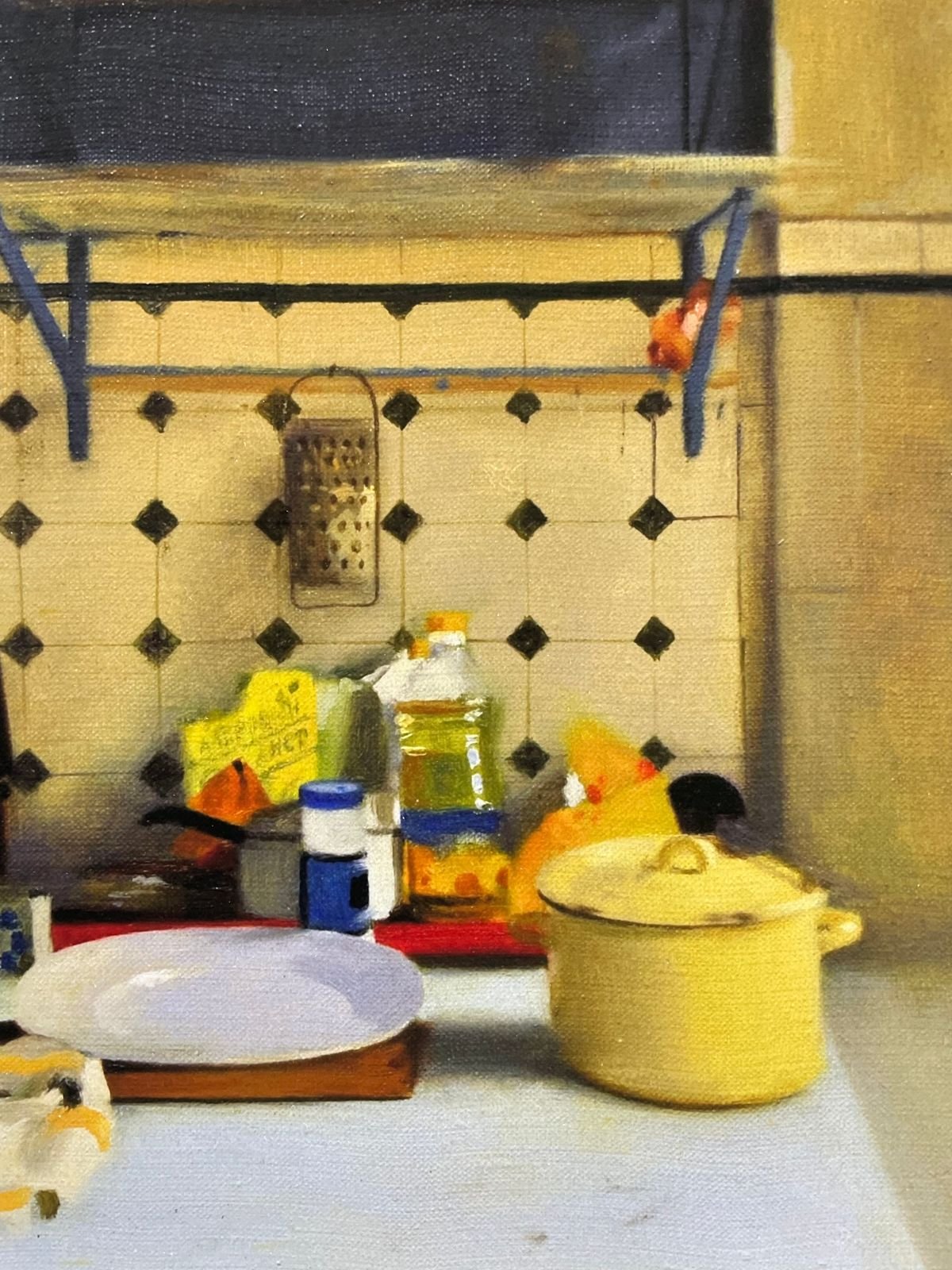

Yet, even as I grew and became invested in my own cooking, I never gave the origins of the broth much thought. This all changed a couple of years ago when I peeked behind the scenes and discovered how deep the lore of Granma’s broth went. I had been living abroad for a few years, so my services as pizza inspector were sadly retired, and my visits had slowed down from once a week to only a couple of times a year. It was a particularly dreich April morning, and after having landed at Aberdeen airport just twenty minutes earlier, I snuck into Granma’s house through the back to try and surprise her. While popping my head round the kitchen door, I saw her bent down over the counter, finely slicing vegetables. Over the years, I had seen little more than a ladle in Granma’s hand, and to see her locked in, holding a small, serrated knife and doing food prep, nearly floored me. I quietly drew in my breath and, in my most outlandish imitation of her Doric tongue, asked:

“Fit ye deeing Granma?”

She didn’t even jump. Her dry cackle ricocheted off the brown kitchen tiles and rattled around the scullery. She always enjoyed experiencing the flavour of her accent passing through the lips of her Grandsons, even if it was only to take the piss. Turning round with a sparkle in her eye – we hadn’t seen each other in half a year – and pointing the knife at me, she beckoned me over.

“Dinnah be daft. Came away and see.” Before her were three large, different mounds of Michelin-quality sliced and diced vegetables: onions, leeks and carrots. For a second, I was confused, looking at a small pile of a strange beige substance, until the half-neep in Granma’s other hand came into focus.

“I chop ‘em all very wee, add the broth mixture, beef broth, then let it slowly ceuk fir three ‘ours.” She pinned the neep down and cut out a thin slice, placing it next to the bag of broth mix.

“What? Three hours.” I laughed in disbelief. She threw me one of her broadest cheesers, then started as if remembering something. She shuffled quickly over to the cupboard and reached for the biscuit tin.

“Come ben the hoose. There’s a fine calt can o’ coke in the fridge if you wan’ it.”

I smiled, still shaking my head with a grin. I reached into the fridge, knowing that I would only take a few sips before the thick syrup would coat my teeth, dry out my gums and make me gag, but I knew how much the destruction of my teeth made her happy. Say what you want about dental care in Scotland, but these dentists have had their work cut out for them up against all the old ladies in the country. I cracked the cold red can, letting the familiar hiss transport me back ten years as I shook my head, still in disbelief and followed Granma’s tiny figure through to the living room.

For the rest of the day, I shook my head, and I shake it now. Granma, who had never given off a whiff of any kitchen prowess, had just transformed into a seasoned chef right before me. I had never thought of where the broth came from. It was just always there. Granma’s broth it was called. Granma’s broth that she had brought to every Christmas, every birthday, every Sunday lunch. The same broth she had sent my dad down to Glasgow with, every time he went to visit my brothers while they were studying. The same broth that had taken up my freezer in my shared London flat and always saved me a meal when the rush of the city enveloped the hours around me. The same broth that I can still taste if I close my eyes and remember how the carrots melt away in my mouth, as the hours always did at Granma’s.

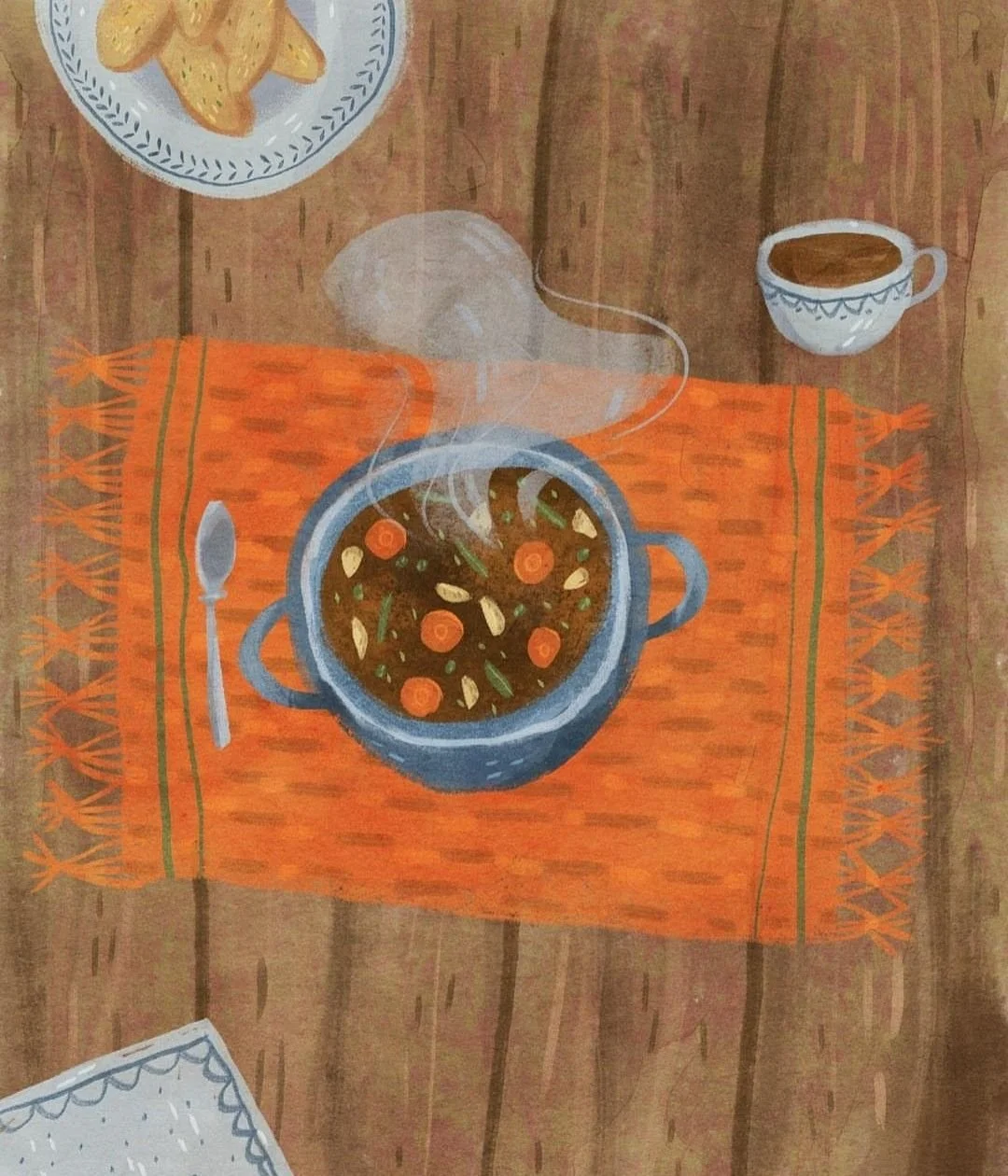

I can picture her, sitting on the edge of her armchair, her scalding hot cup of tea clutched tightly between her palms. Maybe every fifteen minutes, she would get up and shuffle towards the kitchen, her pace slowing with the years. I imagine her walking towards a large twelve-litre stainless steel soup pot, the lid about the height of her chin. She’d pick up a large wooden spoon, whose use was limited to this task alone. As the bubbles threatened the surface of the soup, she would plunge the rough old spoon in and give everything a few slow stirs. As all the leaks, carrots, onions, neeps, broth mix and beef stock settled down, she would shuffle back through to the living room and return to her perch on the edge of the cold leather armchair; the scalding cup of tea, for it was always scalding, clenched tight between her fingers.

Every time we enjoyed the broth, she had gone through three hours of this ritual, pouring her love and time into it and imagining the joy on her grandsons’ faces as they slurped it down. Her grins grew with the years, even as we all fleeted away. But whenever back, alone or together, we would always go straight from the airport to her wee house in Hazleheid. We would sit on the sofa, the wee dinner desks too short for the height of our knees, our heads bent down low, fully immersed in the warm delight of the broth. Spoons would rise slowly to our mouths as we would say melodically between slurps, “beautiful, just beautiful,” as she sat cackling on the edge of her sofa, a huge grin cracking her face and a scalding cup of tea clasped tightly between her fingers.